The editorial staff of Snowy Egret prefer to publish writing which focuses on human interaction with the natural world as it is or was rather than as we might imagine or wish it to be. Therefore we favor pieces which celebrate flora and fauna in their natural states rather than in domesticated settings, and we look askance at anthropomorphic and anthropocentric description or narration, though we acknowledge the human bent in that direction. Note the spirit of this passage from William Stimson's "Turning Back":

I was coming down from the high montane cloud forest, following a mountain stream though the rain forest that covered the north flank of the Cordillera, when all of a sudden I turned a bend in the stream and was abruptly startled by a complete change in the forest all around me. All summer I had been finding new species of Lepanthes orchids along streams just like this one. But when I turned this particular bend, I was assailed instead by a startling and abrupt impoverishment of the forest. The greenery was still there, all around me. There were just as many trees. There were just as many plants. What was missing, though, was the diversity. They were all the same trees, all the same plants. The stream was clogged with a species of sedge introduced from the Old World that I had seen cultivated as an ornamental down in the coastal towns (Cyperus alternifolius). Gone was the primeval richness and diversity that I had been walking through just a second before. I knew what to expect, but I walked on anyway, just to see. And indeed, I didn't have to go far before some wooden shacks came into view. When you got near civilization, the richness disappeared.

We also recognize the inherent irony in a self conscious attempt to be objective in describing the human place in the universe. Nevertheless, we favor the humility of the observer who prefers to experience nature to the hubris of the activist who wants to change it. There is the story of a philosopher who insisted that a tortoise be repositioned in the exact spot where it was discovered in order that the natural course of events not be disturbed by his passing. That is the philosophical bent that we favor in spite of our knowledge that our passing is in itself an event and may cause significant changes in the local environs.

Otherwise, we look for arresting description and observation in respectable linguistic dress. We try for accuracy in scientific detail though we may allow some license for literary effect. We would like not to be the pedants who reject a Keats sonnet for its naming of the wrong explorer rather than appreciate its depiction of astonishment at the sight of the Pacific Ocean.

An example? Try a passage from "The Thaw" by Samuel Lucy:

All sounds and smells this morning, as moisture fights moisture. Fog thick and soupy, blocking out shapes and terrains of land. The drakes whistle, purr, and eeek as they taunt one another. Their hooded heads give them the appearance of little knights, confidence at a seasonal high. Having made the precarious, thousand-mile journey back, they should feel proud. Now they can relax wings and really go to work with their emotions. The hens: they glide deftly in and out through the reeds and alder bushes, staying mostly hidden and out of the drakes' reach. For their part it appears they can afford to be choosy.

Or another? From "Sightings" by Nina L. Pratt:

I crept along the edge of the marsh toward the sound until I saw the large, stocky, brown bird, standing stiffly erect in a secluded tidal pool, head lifted to the sky to expose a brown-and-buff striped breast and a streak of black from bill to shoulder.

And as for the fuzzy borders of anthropomorphism, note that we did print the following from Tomas Filer's "A Sighting":

He [a young sea lion suddenly accompanying the narrator on a swim] lingered a touch longer, keeping pace as I dug in hard with my flippers. 'Hello?' I said. Well, I talk to my dog and the bluejay who eats lunch with me; why draw lines? But I was getting worried. What was up with this youngster? His bulbous black eyes seemed a bit too shiny, were looking personal. 'Hey, I'm not your momma. Are you okay? You're not sick, are you?' The last thing I needed today was a sick sea lion. He dived again. Gone. Good.

Our readers expect to be shown the natural world rather than told about it. Therefore most polemics would fall on the deaf ears of a sympathetic audience. If, on the other hand, you know you have a fresh view of an ancient site or fresh insight into an ancient view, we'll enjoy reading your submission whether or not we are able to use it.

As for poetry, we expect fresh imagery and rigorous shaping of thought. We acknowledge the element of play, but we like to avoid the precious, the esoteric, and the pedantic. We think poetry should make use of the sound, the imagery, and the significance of words at once.

A snippet from Carol Barrett's poem "Rhodies":

Years banked her roots, rows

of notes singing the tendrils

out of her sack. Each wet morningshe spilled uncurled leaves

to the sun. Thirty feet now

and still thirsty, her blossomsswim the windows when it rains.

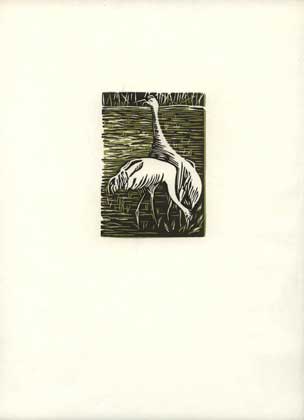

And James Armstrong's poem "Heron":

Up to his backward knees

in the silken wash,

the color of ash, he is two

characters at once:

the original,

upright, relentless, still

god of fishermen, a walking spear,

and the blue messenger.

He wades in morning light, against the horizon

where perfect clouds

are pushed by the wind. Gulls

wheel in the long shadows of the dunes.

Suddenly he unfolds

his cloak and with exaggerated slowness

withdraws each leg

from the surf, doubles his neck,

suspends himself from the sun by wires,

and leaves without speaking...

In subject we look for the same as in the prose: human interaction with nature--honest, direct, and experiential--focused on creating images rather than extolling ideas or advocating causes, though nothing in language is purely one or the other. Show us your best work and we will give it our best read, acknowledging that failure in either case is possible but not calamitous.

All text and images bear the copyright of Snowy Egret and may not be used in any form without permission.